- Home

- Robert Terrall

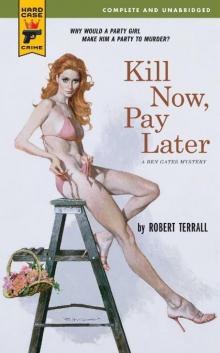

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Page 7

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Read online

Page 7

“All right, Mr. Pope. Now I’d like to ask you about Shelley Hardwick. I understand she was engaged to Dick?”

He circled the question before deciding it was safe to answer. “Here again I fail to see a connection. Yes, she was. My feeling about the engagement is that Dick is well out of it. Shelley is one of my daughter’s closest friends. Mrs. Pope and I both tried not to let Dick realize how we felt, but it was obvious that she wasn’t suited to him at all. Perhaps they are too much alike. They seem to goad each other on, as though in competition to see which can think of the wildest, the most outrageous and irresponsible—no, that makes it sound romantic. To put it prosaically, Dick’s worst scrapes have been ones he and Shelley got into together. That’s why I thank God they’ve broken up at last.”

“What kind of scrapes?”

He made a groping gesture. “I see you’re not a reader of the New York tabloids.”

I stood up. I could think of several other things I ought to know, but they would have to wait. “That’s all for now. Do you want to give me a five-hundred-dollar retainer?”

“Of course.”

He took out a checkbook and wrote me a check.

“I’ll show this to Minturn,” I said, waving it to dry the ink. “If you see him, tell him I’m not one of the bad guys any more.”

“That’s unnecessary. Lieutenant Minturn is sensitive to small changes in the atmosphere. You understand that I want anything you find brought to me first, Mr. Gates. Anything at all that bears on the missing money.”

“Sure,” I said. “That’s the big thing you’re buying with this five hundred bucks.”

He may have given me a sharp look but again it was wasted on me because of the dark glasses. He was pouring himself another drink when I left.

I went back downstairs without meeting anybody and knocked on the door of Anna DeLong’s office. She called to me to come in.

The undertakers were gone. She was at her desk, and Dick Pope was sitting across the room, hunched forward, hands between his legs. He looked up sullenly.

“What did he say?”

“He said you shouldn’t try to beat me up any more. I’m looking for Minturn.”

“He went back to the barracks,” Miss DeLong said. “I think he was afraid you’d want him to apologize.”

Dick got up and went out, coming down too emphatically on his heels. The red patch on each cheekbone had widened. Apparently he had been taking some more of the tranquilizing medicine that sells for six dollars a fifth.

“That seems to have been quite a skirmish in the bathhouse,” she said. “Sonny is up and about, but Binge Palmer may have to go into a cast, as I know you’ll be sorry to hear. Did Mr. Pope succeed in hiring you?”

I sat on a corner of her desk. “I’m not hard to hire. All you have to do is offer me money. How does his tax case stand?”

She had a long sharpened pencil in one hand. She reversed it so the eraser end was down.

“I’d better let him answer the financial questions. But there’s one thing I would like to say.” She reversed the pencil again. “Go easy on Dick, Mr. Gates.”

“Did he tell you I’ve been picking on him?”

“No, he didn’t try to pretty anything up. He doesn’t mind feeling guilty about things, in fact he rather enjoys it. And his motives were good. The way it turned out was a bad blow to him. This friend of his, Binge, has done a lot of boasting about the skills he picked up as a Marine, and Sonny was quite a ferocious hockey player in school, I understand. Poor Dick is quite crushed.”

I started to say something, but checked it in time, seeing that she was serious.

“I’m not asking you to let him out of anything,” she said. “Do what you have to do. But he’s a little breakable right now, and I don’t want him to be hurt.” She looked away and added, “I’m quite fond of Dick.”

I said carefully, “Does this have anything to do with the broken engagement?”

She came down too hard on the point of her pencil, and it snapped. “Dick should never have thought about getting married to anybody. He has too many things to work out first.”

I waited, but when she didn’t go on I said, “Tell him to go easy on me, too. I’m feeling a little breakable myself. Now I’d like to take you over some of the same ground you’ve probably already covered with the cops. Working for Mr. Pope, did you ever put anything in the safe in his wife’s room?”

No, she hadn’t. Her replies to my next few questions were equally brief and abstracted. When she volunteered that she was fond of Dick Pope, who was a few years younger than she was, recently engaged to someone else, and in my opinion quite a mess, I had expected a little more frankness, but that was apparently my confidence for the day.

The wedding presents had been packed and carted off to a bank vault, and Davidson and I used the library, working hard for a few hours without accomplishing much. No one could throw any light on how the knockout medicine had found its way into my coffee, or how the coffee pot had found its way from the library back to the kitchen. No one had known of Leo Moran’s existence before the moment he was shot, or if they had they wouldn’t admit it.

“It’s beginning to blur, Ben,” Davidson said as he took one of the maids to the door. “You slept all night. I didn’t. Let’s go home.”

“O.K.,” I said.

“What did I hear you say?” he asked suspiciously. “O.K.?”

“Are we making any headway here?”

“I doubt it, but I haven’t been listening for the last couple of hours. I’ve been wondering why we don’t talk to Shelley Hardwick.”

“She’s next. I’m going to give her a ride to town.”

“If you want her to talk sense you’d better hurry up, Ben. The last time I saw her she was well on the way to Happy Junction.”

“Oh, God.” I rubbed out my cigar in the ashtray. “I want that girl to communicate. Is Minturn still talking to you?”

“He’s a little cool. If I tried to get into the barracks, I don’t think he’d actually throw me out. But, Ben—”

“I want to know what’s come in on Moran. Then could you come back and keep an eye on Dick Pope?”

He looked at me unhappily. “I’ll have to take a couple of bennies to stay awake. I wouldn’t say he’s the type that goes to bed early.”

“Tail him if he goes anywhere. He’s been pushing the booze all day, and that shouldn’t be hard. I’ll leave word with Mrs. Rooney at the office where you can reach me.”

I phoned for a cab and looked for Shelley Hardwick. I found her in the living room, not far from the improvised bar. Two stern-faced women in black, probably Pope’s sisters, had set up a kind of receiving line. I bypassed it and picked my way among the mourners, who were gathered in awkward groups, drinking and making conversation until they had been there long enough so it would be polite to leave, or had drunk enough so they wouldn’t want to. One of the few people who seemed to be enjoying this curious ceremony was the tall youth named Sonny. Wearing a head bandage, he was talking in a low enthusiastic voice to Shelley, who had given him the crack on the head that had made the bandage necessary. She listened with a dreamy smile. Her suitcase was on the floor at her feet.

“But the whole point is,” Sonny said, “that dreams are connected in a hell of a complex way with the subconscious memory of the race. That’s where Jung busted up with the old man. And Fromm—”

“Shelley,” I said.

She looked up from her drink, which she was holding in both hands, so no one could take it away from her. “Are we ready?”

“I left my car in Prosper,” I said. “A taxi ought to be here in a couple of minutes.”

“Do you two know each other?” she said. “This is—That’s right. You did meet, didn’t you?”

“How do you do?” Sonny said, and continued, “And where Fromm differs from the other boys—”

“Sonny, go get Ben a Scotch. Don’t tell Dick who wants it. He’s probably still nursing

a grudge.”

I picked up her suitcase. “I won’t have time for a drink. Bring yours, you can finish it outside.”

She was open to any reasonable suggestion, and she considered this reasonable until Sonny topped it with an even more reasonable one—that we go some place where they had dancing. It took me ten minutes to argue her out of that, and by then I was thinking of asking for the loan of her high-heeled shoe. Sonny wandered off. We received some disapproving looks on our way to the door, for which I couldn’t blame the people. We were obviously neither of us in mourning for anybody.

Dick overtook us in the hall. “Leaving?”

“Ben’s driving me,” Shelley said. She patted me under the left arm. “And he carries a gun, too. I felt it last night. So nothing can happen to me, isn’t that nice?”

“Shell, I have something that belongs to you. Do you want it?”

“What?”

He grinned. “Have a drink with me and I’ll tell you.”

“Oh, you’re so brilliant,” she said. “But not quite brilliant enough. I’ll come out for the funeral tomorrow and you can give it to me then.”

She pulled me by the sleeve and we walked away.

“What was that all about?” I said.

She giggled. “Haven’t you realized by now that I’m a very mysterious girl? Don’t bother your head, Ben. Richardson Pope, Jr. makes almost no sense the first thing in the morning, and he makes less and less as the day goes on.”

The taxi was waiting. The driver and I recognized each other. He was the one I had told to wait outside Hilda Faltermeier’s that morning.

“Hey—”

“I’ll pay you,” I said. “I’ll pay you.”

“You’re damn well told you’ll pay me.”

So I paid him. I thought his figure was a bit high, but from this point on I was spending expense account money, which can’t be compared with regular money.

As we made the turn at the foot of the drive, Shelley swayed against me, putting her head on my shoulder and one hand against my gun. She said something like, “Ummm.” Then she said, “That was quite a transformation. You were the world’s most unpopular man this morning, and now everybody seems to think you’re great. What happened?”

“I won them over,” I said.

“Was that my lipstick you were wearing, incidentally?”

“Yeah.”

“I thought I recognized the shade.” She gave another low laugh. “I really must have craved that diamond bracelet. I thought afterward that I should have told the trooper I was responsible for the champagne bottle and so on. Then I don’t know, I got sidetracked.”

“Never mind,” I said. “Men are never supposed to claim they’ve been raped.”

She drew back. “Did we—”

“No, no. Figure of speech. How much do you remember of what happened last night? Why did Junior knock you down?”

She pulled back all the way, leaving my gun alone. “He knocked me down! Why, the son of a bitch! What did he do that for?”

“You made some kind of cryptic remark about White Plains. That’s all I know.”

“Well, that accounts for part of it,” she said. “I thought I’d passed out, and it scared me. If I’m going to start blacking out at my age I’ll have to stop drinking, and that would be a shame. Nothing interesting ever happens to me when I’m sober.”

“Do you remember going to bed?”

“Vaguely. It seems to me I got upstairs under my own steam. It also seems to me that I played tag with somebody in the hall, Binge or somebody, but it’s all confused. I’d make a horrible witness if I had to testify. I had an embarrassing session with Lieutenant Minturn. I’ve never seen a man so disgusted with anybody.” A giggle broke through. “Did you notice those teeth? They glared at me, Ben.”

Another thought struck her, and she looked at me more closely.

I said, “No, mine are my own.”

“That’s a relief.”

“Over there, driver,” I said.

He halted the cab in front of the supermarket and I paid him another fare. I took Shelley to my Buick.

“Be right with you. I’ve got to make a couple of phone calls.”

There was an outside booth at the edge of the parking area. I dialed several numbers before I got the one I wanted, and then I was twice given the wrong extension and the waiting cost me another dime. Finally a man named Darcy answered. I told him my name.

“I’d better make sure I’ve got the right extension this time,” I said. “This is the Intelligence Unit? You’re in charge of preparing income-tax prosecutions in the Southern District?”

“That is correct.”

“I’m working with the State Police. We’re interested in Richardson Pope. Can you tell me the status of his evasion case at the moment?”

“Who did you say you were?”

I went over that again and gave him time to write it down. Then he said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Gates, we’re not permitted to give out that information.”

I made a rude noise. “In other words, there isn’t any case?”

“You might make that inference,” he said cautiously. “But I would like to point out something. Naturally we will now give Mr. Pope’s recent returns a most careful audit. If there is anything amiss, you can rest assured that we’ll find it. So if you have any information, why don’t you bring it in? You may not know that the Treasury is authorized to pay a so-called intelligence fee of—”

I assured him that I knew about it and hung up, not really disappointed to find that my new client, who had told me that his lawyers were negotiating with the income-tax people, had been lying to me. Occasionally that happens, and when it does I try not to let it make me cynical.

Chapter 8

While I had the booth I put in a personal call to Sonia Petrofsky at a New York newspaper. Sonia, an old friend of mine, is the daytime secretary of a night-blooming personal-item columnist, whose working life is spent among press agents and celebrities in various Manhattan saloons. Much of my practice is among the same class of people, which gives us something in common. She has the memory of UNIVAC, the energy of Rosalind Russell, and great charm. We would have been married long ago except that she considers me too young for her. She is fifty-nine.

“Ben!” she exclaimed when I said hello. “I’ve been expecting to hear from you since I saw the papers.”

“I couldn’t use the phone where I was.”

“I’ve got the folders right here. This is quite a mess you’ve got yourself into, Ben, and it doesn’t sound like you. In fact, it sounds so much not like you that it probably didn’t happen. Could I be right?”

“Sonia,” I said, “it’s nice to hear your voice, believe me. I was robbed. The question is, can I prove it? So far the answer is no. What folders did you get out?”

“Richardson Pope, father and son. Go ahead?”

“Go ahead.”

“Well, the father seems to be pretty overprotected by his public relations people. He gives speeches. He gets elected to things. But there’s not much here that wasn’t mimeographed first. His namesake is something else again. This boy has probably given ulcers to several generations of his daddy’s press agents. Every time he gets in trouble the company’s name gets in the paper. He gets in trouble often. You’ll probably want to see these with your own eyes.”

“Give me a quick view from the air.”

“Here’s a slight case of statutory rape. Fifteen-year-old girl, charges withdrawn after getting the necessary newspaper space, no doubt indicating a tidy cash settlement. He ran a Ferrari into a pole and killed the girl who was with him. For that they took away his driver’s license for six months. Fight on the sidewalk outside of 21, like the street fights in East Harlem except that this was between Yales and Princetons. Our boy’s role was a little puzzling because he’s been kicked out of both Yale and Princeton. Maybe everybody turned on him—he spent three weeks in Harkness.”

“I hope there’

s something about a fire?”

“Oh, yes. Let me see—three months ago. A recreation building burned down on the Prosper estate. Mr. and Mrs. Pope were away and Junior was giving a party. Correction, a wild party. What made the fire noteworthy was that a man was burned to death. You read about it, Ben.”

“It must have been when I was working on that proxy fight,” I said. “Did it make the Wall Street Journal?”

“Probably not. The man’s name was Samuel Pattberg, but I don’t think he was important enough for the Wall Street Journal. A self-reliant small businessman, the kind that made America great. He handled dirty movies.”

I heard a faint click, as though one tumbler in a complicated lock was falling into place. But it was only the operator, asking for more money. I gave her some, and said to Sonia, “He was showing movies at Junior’s party?”

“Flaming youth, Ben. After he ran off the films to the enjoyment of all, the party moved on. Dancing. Drinking. Swimming in the moonlight. Fertility rites amid the poison ivy. You know what wild parties are like—the Ten Commandments are fractured rather freely, I believe. Everybody forgot about Pattberg. He’d been paid. The idea was that he’d gone home. Actually he was having a little one-man wild party in the projection booth, locked up with a bottle of hard liquor and all those cans of film. Along around three in the morning he wanted a cigarette, and by then he was too drunk to read the no-smoking signs. Pornographic film is just as combustible as the ordinary kind, if not more so. Goodbye, Mr. Pattberg. The only thing the firemen were able to save was the swimming pool.”

“There’s no doubt about how it started?”

“I guess not. A big bang, and the place went up. They didn’t know Pattberg was missing until they counted the cars and found one left over. At first Junior insisted they’d been looking at old Charlie Chaplin shorts, but Pattberg was traced through his registration. The police knew what he really distributed, and it wasn’t Charlie Chaplin.”

I had been keeping an eye on the Buick through the glass wall of the booth. The front door opened.

I said hastily, “I have to go now, Sonia. Thanks. I’ll be in touch.”

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))