- Home

- Robert Terrall

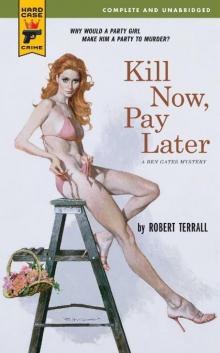

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Page 6

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback)) Read online

Page 6

I washed my hands and face and borrowed his comb. He stood behind me while I combed my hair.

“I guess I know how you feel,” he said, “but I wish you wouldn’t mention it to him, Gates. It would upset him. Don’t you realize why I did it? I didn’t want him to be disturbed.”

“That’s possible,” I said. “But I don’t know if it’s true. I don’t know why you and Shelley were yelling at each other last night. I don’t know who told Moran there was jewelry in your mother’s safe. I don’t know why Shelley walked into this fight. Those are a few of the things I don’t know.”

Shelley protested, “I couldn’t stand here and let them murder you, could I?”

I stooped to look at Sonny’s head. Binge’s jaws were clenched, but he couldn’t keep little injured noises from escaping between his teeth.

“You’ll need something to take your mind off what I’m saying to your father,” I said to Pope. “The Marine needs a doctor. Leave him right here—don’t try to move him. And have the doctor look at Sonny.”

“Hell, you can’t hurt Sonny,” Pope said uneasily. His voice changed as he looked at Shelley. “And as for you, baby—”

“Dick,” Shelley said, “I know it’s expecting a lot, but think, will you?”

She came outside, still angry with me. “What do you mean, you don’t know why I hit Sonny? What’s so hard to understand about it? You don’t know Dick Pope. He wasn’t getting ready to let go.”

“I was just feeling sorry for myself,” I said. “Do you still want to hire a detective?”

“Oh, God. I suppose I said something last night.”

“If you need a detective, I need a client. I’ve got to do something to get some official standing, not that it’ll make much difference to Minturn.”

“I haven’t any money to hire a detective. It was just a crazy idea.”

“Never mind about the money. Wait for me and we’ll talk about it. Maybe I can give you a lift somewhere.”

Chapter 6

Anna DeLong was an orderly looking girl in her middle twenties. She wore glasses, and when I had met her the day before, having that kind of a mind, I had wondered how much persuasion would be necessary to get her to take them off. Her black hair was pulled back severely and gathered in a small bun. That was something else that could be remedied by pulling a few pins. She had unusually clear skin and a calm manner, giving the impression of always knowing exactly where to put her hand on a well-sharpened pencil. If her checkbook ever failed to balance, it would be the fault of the bank. Sometimes, I know, this manner in a secretary is a danger signal. Suddenly, for no apparent reason, she will break the points of her pencils and have to be restrained from walking in and telling her boss what she thinks of him. In Miss DeLong’s case, I thought the calmness was genuine.

She had worn a black suit the day before, to make it clear that she was on the payroll and not a guest, and she was wearing the same suit today, with a different blouse. When I walked into the room she used as an office, she was conferring with my friend Satterthwaite and another gentleman, plainly in the same line of business, no doubt Henry J. Turner himself. An illustrated catalogue lay open at a full-color picture of what was probably the firm’s most expensive coffin.

“Mr. Gates?” Miss DeLong said.

“I’d like to talk to you privately,” I said.

“I’m busy. Is it important?”

“It’s important.”

“Then perhaps these gentlemen wouldn’t mind—?”

“Certainly not,” Mr. Turner said.

“No, indeedy,” Mr. Satterthwaite said.

She came out in the hall with me. “It really has to be only a minute. I have a thousand things to take care of, literally.” She smiled. “It was stupid of the lieutenant to think he could keep you out.”

“I don’t think it was all his idea,” I said. “That’s why I want to see Mr. Pope.”

Her eyebrows went up, though not very far. “About those knockout drops in the coffee. Yes, I heard about it, Mr. Gates, and don’t scowl at me. I’m not at all sure it didn’t happen. What half convinced me is the coffee pot. Who put it away? Not one of the maids. She would have picked up the champagne bottle and the empty glass, and she would have emptied the ashtrays. But how do you expect Mr. Pope to help you?”

“He can call off his dogs.”

“You think Lieutenant Minturn will lie down when Mr. Pope whistles?”

“He doesn’t have to whistle. All he has to do is pucker.”

“Perhaps you’re right,” she said, “not that I think there’s anything reprehensible about wanting to protect our privacy until the funeral is over. After that we can take care of ourselves. How would you go about proving that somebody doped your coffee? I don’t want to seem unsympathetic, but people were streaming in and out of the kitchen last night in droves, few of them sober.”

“Were you?”

“I was the exception. I’ve been reading the newspaper story, and I can see how it would make you wince. But would it have any lasting effect?”

“It won’t last until the year 2000,” I said, “but neither will I. I lose my insurance company business automatically. I can stand that. Not cheerfully, but I can stand it. My big problem is the cops. I need their respect to operate. Not respect, exactly, but they have to look on me as a professional. Most of the cops I know have a pretty primitive sense of humor, and they’re going to think this is the funniest thing since silent pictures. I’ll have to take a certain amount of ribbing. I could stand that too, but when my sources in the department dry up, I’m finished. I’m a one-man agency. I’m close to the cliff as it is.”

She gave me a sober appraisal. “So I can tell Mr. Pope that you don’t mean to let it drop?”

“How can I? You can also tell him that Junior is acting very jittery. He and a couple of friends just took me down to the swimming pool and tried to beat some sense into me.”

“That was silly of Dick,” she said, frowning. “How is he?”

“Physically he’s fine.”

“I don’t think I’ll tell him about that unless I have to. I won’t promise, but I’ll try. You can wait in my office.”

The undertakers looked up as I came in. Mr. Satterthwaite said accusingly, “She hadn’t been trying to get me on the phone at all.”

“I know,” I said. “I was lying.”

I saw the early edition of a New York afternoon paper on Miss DeLong’s desk. I took it to the window. My name is easy to spell, and they had it spelled correctly, I was sorry to see. Minturn was quoted at length. By the time I finished with the front page and followed the story to page five I was feeling my bruises.

Miss DeLong was gone ten minutes. Mr. Turner and Mr. Satterthwaite fidgeted in silence. She opened the door and beckoned.

“He’ll see you, Mr. Gates. But you won’t stay long? I probably don’t need to say that, because he’s perfectly capable of kicking you out.”

We went to the stairs. The gathering in the living room had grown in size as more friends and neighbors came in to pay their respects, watch the police at work and drink the Popes’ liquor. Some were probably left over from the wedding. Except for the time of day and the high-necked dresses, it might have been a cocktail party instead of a wake.

Miss DeLong was walking quickly, a step or two ahead of me. I didn’t know where she fitted into the net of relationships in this house, but I didn’t let that interfere with my appreciation of one of the nicest sights afforded by modern civilization—a good-looking girl going upstairs in high heels and a tight skirt. At the top of the stairs she looked around. I don’t know if she was pleased by my attention, but she was aware of it. She smoothed her black hair.

We passed an open bedroom. Minturn was sitting on a lady’s chaise-longue, looking suspiciously at an open notebook. I recognized the expression, having seen it on the faces of other cops the morning after a killing: he wanted to make sure he hadn’t forgotten anything obvious before he

went home.

“Excuse me a minute,” I said to Miss DeLong, and stepped into the room. “Is this where it happened?”

Minturn’s face darkened. “Gates! Goddam it, it’s beginning to seem that you’re really hunting for it.”

He snapped the notebook shut and started to heave himself to his feet. Miss DeLong remarked coolly from the doorway, “Mr. Pope wants to see him.”

Minturn, halfway up, paused for an instant. To sit down again would have been undignified, so he continued to straighten. Then he had nothing to do but watch me as I looked at the dressing table and the safe, which was still open, and poked into the closet. There was nothing to see, but I stayed long enough to make my point.

“Interesting,” I said.

I went back to the corridor. Miss DeLong knocked lightly at the next door. When a voice called to come in, she opened the door and let me go in alone.

It was an office and bedroom combined. Mr. Pope was sitting in the angle of an L-shaped desk. On it I saw several bundles of letters, an untouched lunch tray, a half-filled bottle of whiskey and numerous bottles of pills, probably manufactured by his own company. He was wearing tinted glasses, a kind of smoking jacket, out at the elbows, with a dark scarf knotted around his neck. His sparse gray hair was neatly parted.

“Sit down, Gates. Scotch?”

“Thanks,” I said, moving a side-chair closer to the desk.

“Help yourself. There’s no ice.”

There was also only one glass, and he was drinking out of that. He waved toward the bathroom.

“There’s probably one in there.”

I found a toothbrush glass, rinsed it out and poured Scotch into it.

“My doctor forbids me the consolations of whiskey,” Mr. Pope said. “But in some ways today is exceptional. I suppose a certain amount of drinking is going on downstairs?”

“That’s the way it seemed to me,” I said. “Nobody offered me any.”

“Let us be charitable. They’ve come to find out if there is anything they can do. Yes, there is something they can do, but I’m afraid they wouldn’t thank me for telling them. I want no part of it. Two of my sisters are down there. They can pass the cheese tidbits.”

He studied me as I drank. I studied him at the same time, but there is little point in studying somebody wearing dark glasses. All I could see was a small image of myself in each lens.

“My secretary tells me you’re going to be a problem,” he said.

“Not necessarily. I just want permission to ask a few questions.”

“So far I understand that the natives have been rather unfriendly? And apparently you think I dropped a hint or two to Lieutenant Minturn?”

“Didn’t you?”

“It wasn’t necessary. Minturn is an intelligent officer. He is satisfied with what he takes to be the facts. So am I. I see no profit in pursuing it any further. Neither does he. But I believe you disagree?”

“Damn right I disagree.”

“And in addition to your other difficulties, you have had a set-to with my son?”

“He asked me not to tell you about it.”

“From that I can guess how it went. Dick has never been lucky in his attempts at self-assertion. I believe Miss DeLong is right, you will be a hard man to ignore. But I’m still not sure exactly what you want.”

“Didn’t she tell you? I’d like to find out who was working with Moran. And it won’t be enough to find out. I have to get it in the papers.”

“Are you under any legal pressure? Has anybody threatened to sue you for negligence or revoke your license?”

“It’s been mentioned. I don’t think it’s serious because there wasn’t any loss. This is just something I have to do if I want to go on being a private detective.”

Mr. Pope rattled his fingers against the desk. “And you do want to go on being a private detective?”

“I think so. I don’t know of any other job where you meet so many peculiar people.”

He swirled whiskey around in his glass, admired it against the light, and drank some of it. “Miss DeLong made a tentative suggestion. In the pharmaceutical business, as you probably know, dog eats dog. My company maintains a so-called trade research department which sees to it that we are never unpleasantly surprised when one of our competitors brings out a new product. Would work of that kind interest you?”

“It might,” I said, “if you gave me a thirty-year contract. I doubt if you will. In six months, after things have cooled off here, I think I’d be unemployed.”

He went on rattling his fingers. He was probably looking at me, but because of the dark glasses I couldn’t be sure. “And if I ask Lieutenant Minturn to assign me a trooper with orders to arrest you on sight for trespass, how will you proceed?”

“I’ll check it at the other end, through Moran.”

He leaned forward. “Gates, I am strongly tempted to—”

I broke in. “Before you start threatening me, Mr. Pope, don’t you see how it looks? Press on it some more and even Minturn may get it. You people are covering up for somebody. I don’t care about that—I’m not the Lone Ranger. But you know my problem. Think of some reasonable out and I’ll go away and leave you alone.”

“I can’t think of any,” he said after a moment. “Can you?”

“Just the obvious one. Let me look around and see what I turn up.”

He sighed. “Then if I am to have any control over you at all, I’ll have to hire you. Have another drink.”

“No, thanks. I haven’t had breakfast yet. Hire me to do what?”

He took his time. “Is there any possibility that you can respect a confidence, Gates?”

“There’s a faint possibility,” I said. “I’m not very talkative.”

He listened to the pleasant sound made by whiskey as it leaves the neck of a bottle and falls into a glass.

“I wonder what delusions you have about the relationship between Lieutenant Minturn and myself. I happen to own a substantial property in this county. I admit to playing golf occasionally with people who have political influence. But this is a capital case. Two people have died, and if you think that Minturn would close down an investigation unless he was completely satisfied with what he had found, you are mistaken. He reconstructs the crime rather simply. Moran stole my wife’s jewels, then went down to the library to steal my daughter’s. He was shot to death, the loot was recovered. But one thing I didn’t mention to the police. There was more than jewelry in the safe in my wife’s room. There was seventy-five thousand dollars in cash.”

Chapter 7

He mentioned the sum casually, as though only a social misfit would neglect to keep a small amount of cash around the house for an emergency, such as having to pay the paper boy.

“Why didn’t you tell Minturn?” I said.

“He didn’t ask me.” He hesitated. “I am having difficulties with the income-tax people. My lawyers are in the middle of some delicate negotiations right now, and my possession of such a sum in currency might be misunderstood. I’m hoping that Minturn won’t get wind of it.”

“How did you keep it, in loose bills?”

“In two large envelopes. A few thousand-dollar bills, the rest hundreds. Nobody knew it was there but my wife and myself.”

“And you want me to get it back?”

“Without letting anybody know it was there, if possible. I will pay your regular fees and expenses, plus ten percent of any amount you recover.”

I must have looked surprised. Seventy-five hundred dollars was a large fee for me. He said gently, “So you won’t be tempted to turn the case over to Internal Revenue for the ten percent they pay informers.”

That was a nice touch. “I accept,” I said promptly. “And now that you’re a client, can I ask you a few questions?”

He took a moment before answering that, which was one of the easy ones. “You’ll start drawing expenses as of now. Don’t be in too much of a hurry. This is a bad day. I’m not thinking too c

learly.”

“I want to get that money back before anybody starts paying bills with it. You probably have some idea who took it?”

He spread his hands. “Not the slightest.”

“How long has it been in the house?”

“That I can’t say with any precision. I make a practice of keeping a certain amount available, sometimes more, sometimes less.”

“Even your secretary didn’t know about it?”

“I’m quite sure she didn’t.”

“How long has she worked for you?”

“Three years. Nearer four. But before you go any further, I can assure you that she had nothing to do with it. Put it out of your mind.”

“Does she work for you in the city too?”

He put his hands on the desk. “I told you to put it out of your mind.”

“That’s what you told me,” I said. “I don’t know why it is, but whenever I ask a simple question, people either go off like a Roman candle or they get very correct. It was Miss DeLong who suggested that I might want some coffee last night. She passed the waitress on the stairs. It may not mean anything, but how can I put her out of my mind until I know more about her?”

He breathed in and out several times before telling himself to relax. “I’ll give you a comprehensive answer, and get it out of the way. Mrs. Pope has been in increasingly poor health. After her second heart attack I rearranged my work so I could do more of it at home. I needed a part-time secretary and a part-time housekeeper, and Miss DeLong asked for the job. At the time she was a typist in the executive pool, at half the salary she now earns. She works two or three hours a day for me. The rest of the time she manages the staff, plans menus and so on.”

“And she doesn’t live in?”

“She could if she wished, of course. She prefers to maintain an apartment in White Plains. Surely that exhausts the subject of Miss DeLong?”

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))

Kill Now, Pay Later (Hard Case Crime (Mass Market Paperback))